FP in Plain English: How Composition & Currying Work

Functional programming is a cool programming style with a lot of neat benefits, but it's also poorly explained and rarely understood. It's mainly because of the lack of intuition in math language. People can't understand you if you sound alien. In this series of posts, I'm going to shortly explain to you some FP concepts in plain and simple, day-to-day English. Hope you find this helpful.

After each section, there will be exercises for you to solidify your understanding of the related topic. The solved version will be provided at the end of the post.

So, what is functional programming

Functional programming is how people write code with functions, pure functions among which should be leaned towards as much as possible. If you don't know what a pure function is, please read on.

Pure Function

What is a pure function

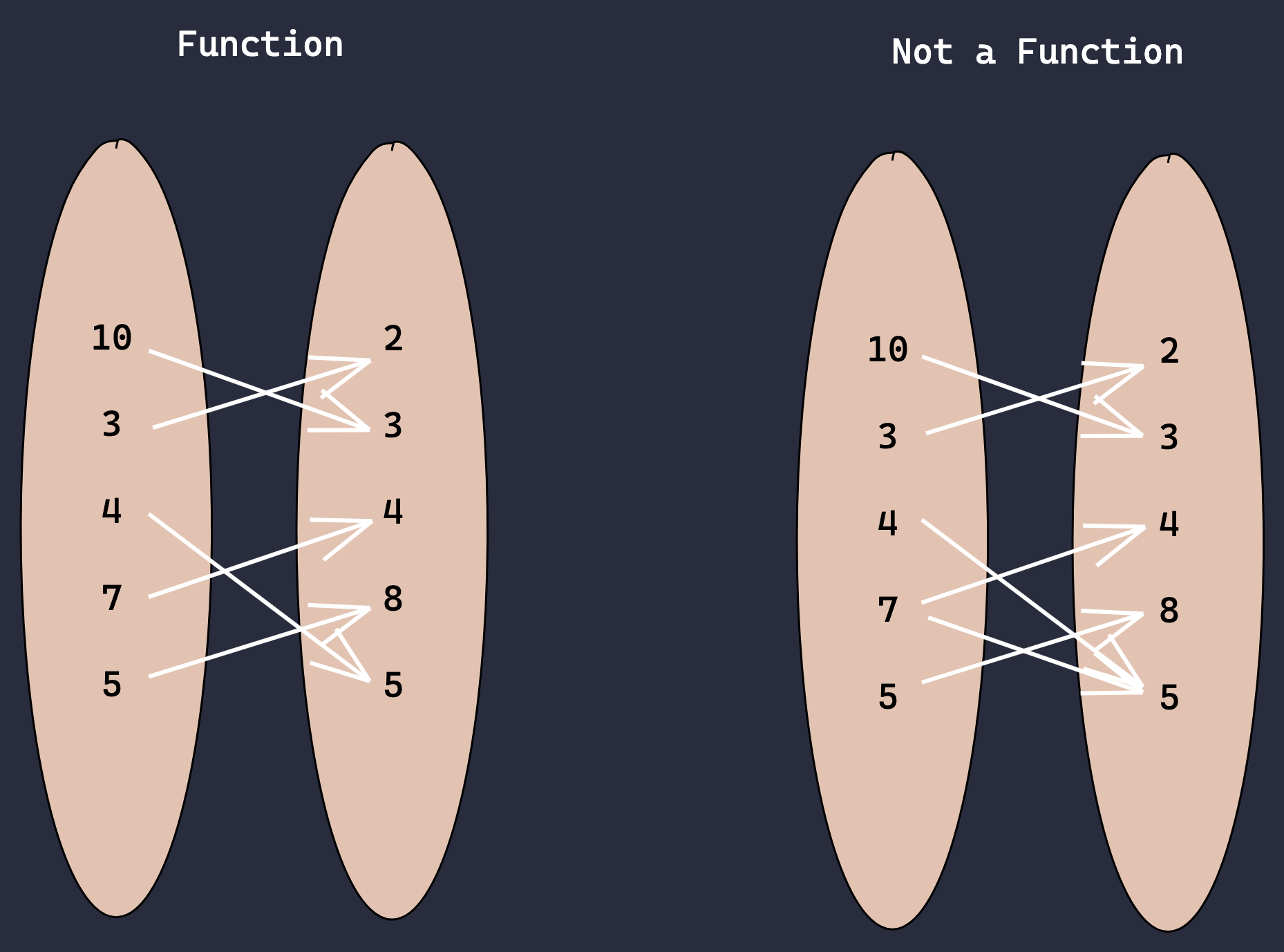

Simply put, a pure function is a relation between two sets of values. A set is just a bunch of things that have something in common and that can be grouped together. In a pure function, for every input, there is always one and only one corresponding output. The inputs, as a whole, are called the domain of the function, whereas the outputs corresponding to the inputs are called the image of the function. When the set containing all the outputs has more elements than the image of the function, the whole set is called the codomain of the function. A pure function only computes one result and does no more than that.

Traits of pure functions

- Total: For every input, there is only one corresponding output.

- Deterministic: Always receive the same output for a given input.

- No Side Effects: Only compute an output value. Won't anything else like changing existing values.

Why use pure functions (advantages)

- Reliable: Behaviors are predictable.

- Portable: Can be extracted and moved around.

- Reusable: Can be used many times.

- Testable: Easy to test.

- Clean: No pollution outside the procedure.

- Composable: Can be pieced together and form new operations.

- Properties/Contract: All the math is available to you.

Can I use impure functions in FP

Yes, you can. Functional programming is not about avoiding side effects but managing them. In fact, in order for you to manage impure functions, there are some specified available computation patterns, such as monads, which we'll learn about later in this series. Functional programming allows impure functions, but it will force you to hide them, so that impurity can be marked and separated and won't affect the overall robustness of the program.

Mathematical Properties used in FP

Associative

This means that the result of an operation will always be the same no matter where you put the parenthesis.

// associative

add(add(x, y), z) === add(x, add(y, z))

Commutative

This means that the result of an operation will always be the same no matter how you move the inputs around.

// commutative

add(x, y) === add(y, x)

Identity

This means that the operation has such a value, with which the operation always returns the same value that is used as its another argument.

// identity

add(x, 0) === x

Distributive

This means that, in the operation, you can split an argument, take its bits and pieces, apply the same operation to them with other arguments, and put the separated result together into one as the final result.

// distributive

add(multiply(x, y), multiply(x, z)) === multiply(x, add(y, z))

After understanding these concepts, you can move on to actually write some code with some FP techniques, one of which is good old currying. It might sound weird at the first glance. But it's actually surprisingly easy to grasp. Just read on and make sure to try out the code example for yourself.

Currying

What is currying

Currying is the process of transforming a function that takes many arguments into a function that takes one argument at a time.

Why need currying

We can use currying to preserve an intermediate result during an operation. In another word, we can use currying to save the progress of an operation. For example, here we have a add function that takes two arguments altogether.

const add = (x, y) => x + y

Simple, right? But now what if we want to add one to a number many times? Well, one solution is to write it the same way, like this:

const add1 = () => add(x, 1)

In a simple use case like this one, your code might work just fine. But what if what we have is a super complex computation extremely hard to make sense of? What if what we want is not only one variation but many ones? The complexity can skyrocket beyond your control in a short period of time, and therefore we need a way to manage it so that we preserve our sanity. Currying is one of the techniques we can leverage here. With currying, the add function might look like this:

function add(x) {

return function (y) {

return x + y

}

}

// or

const add = (x) => (y) => x + y

// or

const add = (x) => (y) => x + y

This way, when we want to reuse the code with some value, we can pass the value to the curried function and use the partial function application, meaning applying a function with some arguments fixed, just like this:

const add2 = add(2)

add2(40) // 42

// you can take this function and reuse it however you want

const addx = (x) => add(x)

An example not so trivial would be like:

const curry = (f) => (x) => (y) => f(x, y)

const isOdd = (x) => x % 2 !== 0

const filter = (f, xs) => xs.filter(f)

const curriedFilter = curry(filter)

const getOdd = curriedFilter(isOdd)

const result = getOdd([1, 2, 3, 4])

console.log(result) // [1, 3]

There are many existing solutions for doing functional programming in JavaScript. So we can use curry in Ramda, a popular third-party library. This curry method is much more robust and optimized in terms of performance.

import {curry} from 'ramda'

const replace = curry((regex, replacement, str) =>

str.replace(regex, replacement)

)

const replaceVowels = replace(/[AEIOU]/gi, '!')

const result = replaceVowels('I have a pen.')

console.log(result) // '! h!v! ! p!n.'

A side note on currying

Just so you know, currying is a fundamental pattern used in Haskell, a famous functional programming language. The whole language depends on it. We can demonstrate it with a type signature in Haskell, which looks quite like an arrow function:

inc :: Num a => a -> a

Why the name "currying"

The name "currying", coined by Christopher Strachey in 1967, is a reference to logician Haskell Curry.

That's all you need to know about currying to understand the rest of the concepts. I might do another post concentrating on this topic in the future and talk about how we can take it to the next level, but let's not get ahead of ourselves just yet.

Point-Free

Point-Free is a programming style where a function definition does not even mention information regarding its arguments. In the examples above, because of currying, information about the arguments is extracted away in the middle and will only appear at the last step of the computation. This makes your code more predictable and easier to debug since you don't have to worry about the inputs until the end of it.

Partial (Function) Application

This simply means to call a function with some of its arguments fixed and some not. But note that partial applications are not exclusively used with curried function. For example, you can use the built-in partial method in Ramda to perform a partial function application. Just like this:

import {partial} from 'ramda'

const multiply2 = (a, b) => a * b

const double = partial(multiply2, [2])

double(2) // 4

Composition

Composition is the action of passing a function as an argument into another function to form a new function. You can think of it as nesting functions together. Because that's really what it is. It might look more familiar to you in JavaScript. So let's define a simple compose method:

const compose = (f) => (g) => (x) => f(g(x))

As you can see, in compose we pass function g into function f so that we get a brand-new function. Pretty neat, huh?

What's nice about composition is that it's also associative. Because we can also write compose like this:

const compose = f => (g => x) => f(g(x))

Or this:

const compose = (f => g) => x => f(g(x))

A more observable example in code would be like:

import {compose} from 'ramda'

const toUpper = (str) => str.toUpperCase()

const exclaim = (str) => `${str}!`

const first = (str) => str.charAt(0)

const shout = compose(exclaim, compose(toUpper, first))

// is the same as

const shout_ = compose(compose(exclaim, toUpper), first)

// also the same as

const shout__ = compose(exclaim, toUpper, first)

console.log(shout('tears')) // 'T!'

console.log(shout_('tears')) // 'T!'

console.log(shout__('tears')) // 'T!'

The composition works just the same no matter how you use parenthesis in it. If you find it hard to grasp, just think of a pipe with an unorthodox shape. As long as you don't swap the bits and pieces around, you can split the pipe however you want, and it will still hold up and works. Hopefully, this contrived metaphor can give you some intuition on how to think about the associativity of composition.

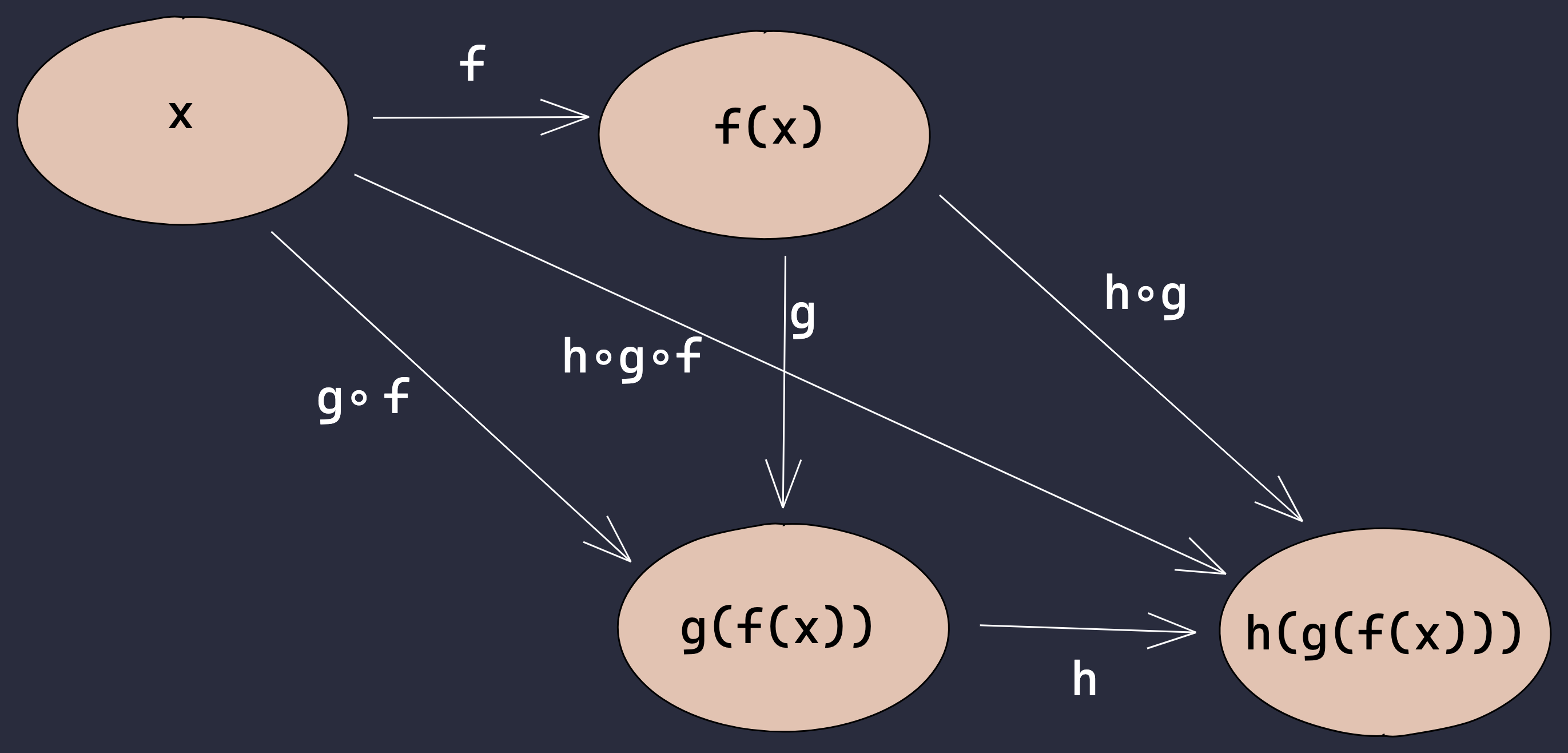

Maybe I should've brought this up earlier, but just for a more intuitive demonstration, I want to show you how I think about the associativity of composition. It's just like a graph with nodes and edges:

Pretty clear right? You might wonder what ∘ means. So in math function composition looks like this: f(x) ∘ g(x) = f(g(x)) . The symbol ∘ is the operator you use when doing function composition in math. And there is also a similar operation, both in math and programming language, called "pipe operator", which is basically the same operation but written in another way. In some functional programming languages, Elixir for example, different from compose, you'll have to reverse the order of functions you are going to call when using the pipe operator. But in JavaScript, the pipe operator |> works just the same as _.compose in Ramda. Yes, JavaScript already has its own pipe operator, which is still in stage 1, but in case you are curious, here is how we use it:

import {compose} from 'ramda'

const double = (n) => n * 2

const increment = (n) => n + 1

// with regular function calls

double(increment(double(5))) // 22

// with compose

compose(double, increment, double)(5) // 22

// with pipe operator

5 |> double |> increment |> double // 22

Now back to what we were talking about. Along with currying, function composition is fundamentally how we build complexity up in functional programming. It is so critical in FP that almost all the FP data structures and design patterns wouldn't exist without it.

And that's all I got for you this time. Just a few cornerstones for your FP journey. In the next one, we'll be looking at some data structure and design pattern goodies, specifically functors and monads. Stay tuned!