How to Build a Mini IO Monad

Instinctively, when we look at a difficult concept for the first time, that ONE question that pops into our minds is usually "what is it". Because asking "what" is such a valuable human nature that helps us protect ourselves from our natural enemy in the old days. And it can be effective if we already know what we could be dealing with. Lions, tigers, or cute puppies. But if this unfamiliar concept is deeper than you thought it would be, you'd better switch your tactics and asking "how does it work", more close to our instincts, "what can it do" or "what can it be used for". By asking the right question, we can just discover the concept ourselves.

In this one, we'll talk about how a monad works by turning our functor example from the previous post into a glorious monad.

const Functor = (x) => ({

value: x,

map: (f) => Functor(f(x)),

})

const number = Functor(0)

Start With Why: Going Pure

Why do we need to enhance our little functor? Well, because its composability is still weak. Let me explain.

What should we do if we want to log something out and chain some operation after that? Now we could use a functor for logging.

number.map(console.log) // 0

This is valid JavaScript with a bit of functional flavor. But it's not authentic enough because we are not using pure functions. Recall that in functional programming, you can use impure functions, but pure functions should be used as much as possible. So ideally, each function we use in every .map should be a pure one. But the function in the first .map is impure due to the logging side effect. So how can we dub it pure? Well, one thing we can think about doing is to delay the evaluation of that function by wrapping the result and the logging effect in another function, like this:

number.map((x) => () => {

console.log(x)

})

This way the function that gets mapped will be a pure one, and the impure function's side effect will only happen when it is invoked later. That's one way to do it. However, if we just pass the wrapper function into the mapping, it would require us to change our the .map API definition, which is not feasible and against the definition for Functors. We would have to unwrap the outer function in the definition, which is not good since we want our API to be as generic as possible.

Another way to fix this problem is to define a Functor just for the mapped function. Like this:

number.map((x) =>

Functor(() => {

console.log(x)

})

)

And, to ensure the function mapping work as before, our Functor definition has to be changed. In fact, we have to change the name of this thing we called Functor because it will not only be a functor from now on. Let's call it Container instead.

const Container = (f) => ({

value: f,

map: (g) => Container(() => g(f())),

})

Notice that we wrap the function composition in an anonymous function to preserve the structure of our Container context. Consequently, our number has to be declared with a function.

const number = Container(() => 0)

And now, everything should be fine. To put everything together, we will get this:

const Container = (f) => ({

f,

map: (g) => Container(() => g(f())),

})

const number = Container(() => 0)

number.map((x) =>

Container(() => {

console.log(x) // 0

return x

})

)

Forge The .chain with .map & .run

Now the logging is working, but there is a problem here. Our mapped result is a functor nested in another functor. To inspect what we got, let's add a inspect method temporarily:

const Container = (f) => ({

f,

map: (g) => Container(() => g(f())),

inspect: `Container,${f().inspect || ''}`,

})

number.map((x) =>

Container(() => {

console.log(x)

return x

})

).inspect // 'Functor,Functor,'

We need to find a way to sort of 'flatten' this functor nesting. How do we do that? If we run the provided function, we will get a single-layer functor. So let's add a .run method.

const Container = (f) => ({

f,

map: (g) => Container(() => g(f())),

chain: (g) => Container(() => g(f())).run(),

run: () => f(),

inspect: `Container,${f().inspect || ''}`,

})

This run method only does one thing: run the provided function. So now we can do this:

const Container = (f) => ({

f,

map: (g) => Container(() => g(f())),

chain: (g) => Container(() => g(f())).run(),

run: () => f(),

inspect: `Container,${f().inspect || ''}`,

})

number

.map((x) =>

Container(() => {

console.log(x)

return x

})

)

.run().inspect // 'Container,'

And we can do other like data requests. I will use a new Container just to simulate the use case.

const Container = (f) => ({

f,

map: (g) => Container(() => g(f())),

chain: (g) => Container(() => g(f())).run(),

run: () => f(),

})

number

.map((x) => Container(() => x + 2))

.run()

.map((x) => ioPure(40).map((y) => y + x))

.run()

.map(ioLog)

.run() // 42

.map(() => ioPure(9))

.run()

.run() // 9

You might notice that we do a run every time the mapping is accomplished. So of course we can simply extract this pattern into a method called chain.

const Functor = (f) => ({

f,

map: (g) => Functor(() => g(f())),

chain: (g) => Functor(() => g(f())).run(),

run: () => f(),

})

number

.chain((x) => Functor(() => x + 2))

.chain((x) => ioPure(40).map((y) => y + x))

.chain(ioLog) // 42

.chain(() => ioPure(9))

.run() // 9

The chain method is what makes a functor a monad. In Haskell, the chain method is called bind, but in JavaScript, to avoid the conflict between the built-in bind method on functions, people tend to use the name chain for this pattern.

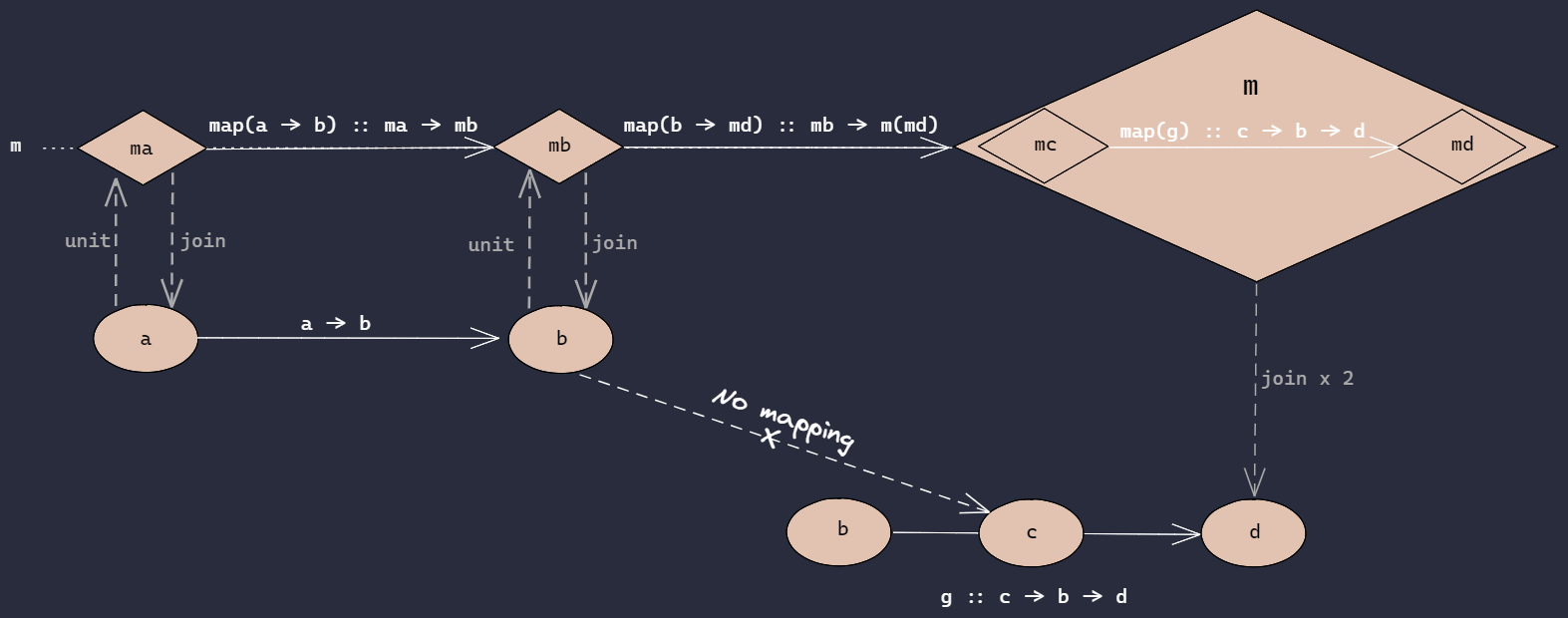

We can visualize a monad like this:

Summary

In short, a monad is a functor that can unwrap its own kind and get out the value inside them.